The Coronavirus Pandemic has changed the way that we live, work and socialise. It is a generationally defining moment which will have a wide-ranging catalyst effect throughout society. Now that lockdown restrictions are starting to relax and we are daring to look to the day when we will be free to travel again, I explore how travel patterns have changed, and how they might continue to change moving forward. I consider the key opportunities we have in light of these possible changes.

The key question to my mind is whether the changes we’re seeing represent a shock or a shift in demand – is this a blip in the way people move, or is this a more tectonic shift in our living, working and travel patterns? During every major transport, and Information and Technology innovation, commentators forewarn the end of the city, or the ‘death of distance’, or the ‘End of Geography’ and yet the world’s urban population continues to grow; air travel rebounded after 9/11, likewise London Underground and Bus usage after the 7/7 bombings, in each case after relatively short-lived periods of substantially-lower demand. That being said, at the time of writing Virgin Atlantic has announced 3,000 job cuts and an end to its operations at Gatwick Airport, after British Airways announced they could not rule out the closure of its Gatwick operations, clearly showing the airline industry considers this to be a major shift in their business.

So, the question is will our transport behaviours change forever – or at least for a long while – or just rebound back?

Mobility Trends

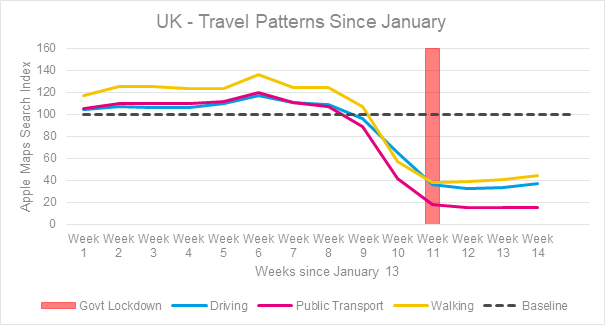

I’ve had a look through Apple’s mobility data, which shows the UK’s relative volume of direction requests based on a baseline volume dated 13 January 2020. If Monday 13 January was a normal day (demand is 100), this data shows the difference in daily direction requests over the next three months.

The data doesn’t show absolute volumes. I’ve taken walking, driving and public transport data searches for the UK as a whole (sadly, no cycling data was available). Data available for Leeds, Manchester, Birmingham and London all show near-identical patterns. To simplify, there are perhaps three phases that can be identified from the UK’s travel patterns in the last three months

Business as Usual – 13 January to 8 March (weeks 1 to 8)

Travel behaviours are ‘as normal’ – people are returning to work from Christmas holidays. Apple Maps searches for walking, driving and public transport trips remains broadly constant throughout the three-month period.

Travel demand and modal choice are driven by trade-offs between the convenience, cost and the accessibility of each mode (amongst myriad factors).

The Rapid Drop – 9 March to 22 March

A sharp reduction in Apple Maps searches for all modes of transport. Most of the reduction in travel demand occurred before the UK’s official lockdown, announced on 23 March.

Personal and public safety becomes the key consideration in travel choices as offices, retail and leisure attractions close.

Lockdown – 23 March to now

Apple Maps searches remain constantly low after the UK Government’s lockdown announcement on 23 March 2020. Public transport searches have (relatively) shrunk the most – a post-lockdown demand of 16% compared to 41% and 35% for walking and driving, respectively. This may in part be due to the way we use different modes – people may be walking as part of their daily exercise, or driving to shops – but there is no denying that public transport is a much less appealing proposition during the pandemic.

Public safety is the key consideration in this policy-backed reduction in travel. Only essential journeys are made as the absolute number of trips is significantly lower than normal. Many people are able to work from home and many shopping trips are avoided by online shopping (there has been an increase in online food retail users of 10%).

Four Scenarios for the Future

What might the next phase of transport demand look like as we slowly transition out of lockdown? Will we see a reversion to the old way – a bounce-back? Or more of the post lockdown trends, as commuters show caution in their behaviour? Or some form of hybrid?

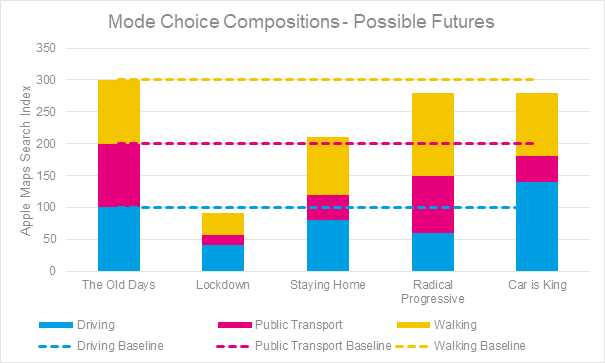

Looking across the board, then, how might driving, public transport and walking modes bounce back? A return to the baseline for each mode would be returning to 100% (totalling 300% between the three modes). I have modelled four scenarios to better understand what might happen. They are not predictions, but designed to help think about four plausible futures.

Scenario one: the old days: Each mode is at 100% – the pre-virus baseline

_

Scenario two: staying home (high probability): As people have invested time, effort and money into making home offices and online shopping work for them, the increase in these practices may be here to stay, resulting in an overall lower frequency of travel. This I think is most likely to affect public transport services, to which people will be most reluctant to return, whereas driving and walking might well remain nearly as attractive as they used to be

_

Scenario three: radical progressive (low probability): as people adjust to walking and cycling more whilst roads are quieter and safer, they don’t look back and don’t return to public transport for everyday commuting needs. Driving demand may be suppressed through road space reallocation to further encourage walking and cycling. A shift from public transport to active travel would free up capacity on public transport services, with lower overall demand and a flatter peak demand (due to flexible working), meaning that public transport would in time, and with the introduction of a vaccine, become a more popular proposition. A rebound to public transport could then cannibalise car travel rather than detract from an increase in active travel.

_

Scenario four: car is king (medium probability): people are unwilling to return to public transport, which is considered a health risk, and private transport is preferred as it’s door-to-door and involves very little human interaction. Whilst the data shows that the driving and walking searches are slightly increasing as lockdown continues, public transport usage remains very low compared to its baseline – two of the three busiest, post-lockdown public transport days were in the week lockdown was announced, contrasted with the fact that two of the busiest three driving days were last week.

The way that these scenarios play out will be radically different in different places – my prediction is that areas where public transport was previously the main mode of transport (central cities, especially progressive places) will see a big growth in active travel, whereas those places that are less well-connected by public transport will see people revert back to car driving. Outer parts of cities, then, may have congestion issues, whereas we may need to look at providing more road space for pedestrians and cyclists in inner cities.

This pandemic presents an opportunity to take stock and to evaluate where we were, are and where we want to be, and this is the time to collectively consider how we can seize this opportunity.

Opportunity 1 – Flexibility

More flexible working hours can be beneficial for an at-strain transport system for a number of reasons – increased working from home means fewer trips and peak spreading, where people work with more flexible hours. This could mean a dispersed rush hour and, effectively, a higher capacity for the transport network as a whole.

This in turn can support more residential density in suburban areas, something encouraged in national and regional policy, to respond to demand on the housing market.

Office design will also be much more geared to flexible work. In many cases, work can be completed anywhere, so offices need to facilitate relationship building, collaboration, and knowledge sharing.

Opportunity 2 – Promoting Active Transport

Whilst the Apple Maps data hasn’t included cyclists, there has been some evidence elsewhere that leisure cycling in the UK has increased during the UK’s lockdown. A proactive rationing of road space, to more closely reflect the substantially lower vehicular demand, might go someway to minimise the effect of a quasi-induced demand as relatively quiet roads and shorter journey times entice people into their cars. This rationing would have a ‘double dividend’ effect – disincentivising car travel and incentivising travel by walking and cycling by providing more safe and dedicated routes.

Opportunity 3 – Polycentricity and Personal Travel

Transport has been a mainframe system – it has been shaped by large, expensive infrastructure predicated on economies of scale. It is now moving into becoming a more personal experience using lighter and more flexible infrastructure to reflect a more consumer-focussed means of using transport services. Where previously transport services were designed to transport workers from the suburbs to their central London offices, now the infrastructure is ‘micro’ allowing people to make different trips to different hubs. Similar to Anne Hidalgo’s 15-minute city concept in Paris, we have an opportunity to rethink our city experience in a way that will be geared towards more multi-modal and active travel to workspaces, retail and leisure facilities closer to where we live, rather than in a single Central Activity Zone.

This may be where mass transport’s lost demand may end up – in using a web of shared, active and micro-mobility options. The way that transport authorities respond to this will be key – in a radical future an authority like Transport for London would continue to act as a regulatory authority for public and private transport services, centralising and managing provision through an App that would enable seamless multi-modal travel and integrated payment.

There are those who will argue that society-wide social changes are notoriously hard to devise and stubborn to implement. They may point to the battle against obesity (famously planned over many generations) or the attempts to address some of society’s great inequalities. Both are slow to change and require life-long societal commitments. But then again, some changes have happened rapidly and have then been sustained over many years or decades. The reduction in the numbers of tobacco smokers and the improvement in air quality in our major cities, would be two examples of radical and sustained changes. And then there’s the elusive category of things which seem to have changed for good, but then do a u-turn and retreat to their former selves. As we look ahead to life after lockdown only time will tell whether this current crisis will cause ‘shock or shift’ – but there are many opportunities for change that may just have been accelerated by Covid-19.