The UK Government announced in March 2021 a national bus strategy which aims to radically rethink the management and operation of non-London bus services in England. These changes form part of a wider picture of government looking to proactively address car dependency in urban, semi-urban, and rural areas.

Taken alongside proposed major reforms to the planning system, new strategies for walking and cycling and recent proposals for design codes, there is a major opportunity for sustainable travel to become an increasingly attractive mode of transport for more people across England.

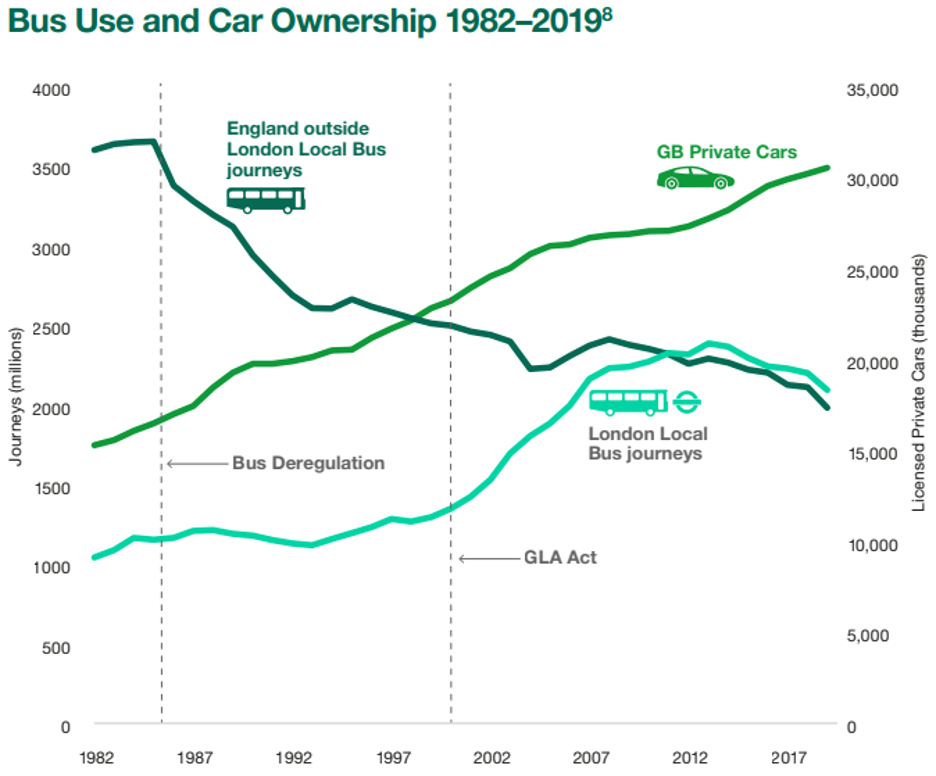

The strategy being proposed by the government signifies the end of the privatisation and deregulation of the bus market in England (outside London) that started in 1986. Contrary to the railways, where the privatisation of 1994 was followed by a prolonged period of passenger growth (although the rail franchising model seems now to have reached the point where a significant rethink is needed), bus usage has been reducing outside London across the whole privatisation period (and since 2015 in London as well).

(source: Bus Back Better – National Bus Strategy for England)

The first aim of the national bus Ssrategy is therefore to support a growth in passengers on the bus network. The key element of change that the strategy introduces is bringing in significantly more local authority control in the development of the bus network: through enhanced partnerships (which appears to be the favoured approach by government), where the network is essentially co-designed between the local authority and the bus operators; or through franchising (essentially the London and, also soon, the Manchester model) where the definition of the network and framework for the services is firmly in the public hand with proposed routes or networks then tendered to bus operators.

A second key element of decline in the bus services has been identified in the lack of coordination and integration. Outside London, it is usually difficult to find a map or a timetable showing the public transport network in a specific area, with operators not including competitors’ services in their maps and timetables. Further, the network is often difficult to understand and use, with convoluted routes, different routes at different times of the week or of the day, complex fares, operators not accepting each others tickets, and issues of bus accessibility.

A key deliverable of the strategy is therefore the integration of the bus network as well as simpler, possibly flat (at least in urban areas) and capped fares. The strategy also mentions multi-modal integration, from park & ride sites, to integration with rail transport, walking and cycling. It should be noted though that the impact of P&R sites on induced traffic and rural transport services utilisation can be controversial as shown by the excellent work of Smarter Cambridge Transport.

The integration with walking and cycling (and to a broader extent with micromobility) is in my opinion currently understated in the strategy: if (as the strategy correctly states) it is unattractive and uneconomical to have bus routes running extended loops in housing estates, then the consequence must be that the catchment area of bus stops has to be extended. Seeing bus stops as mobility hubs including bike storage, bike sharing and services for the new micro-mobility services is key to improving their attractiveness in rural, low density areas.

(source: UK Mobility Hub Guidance, CoMoUK 2019/2020)

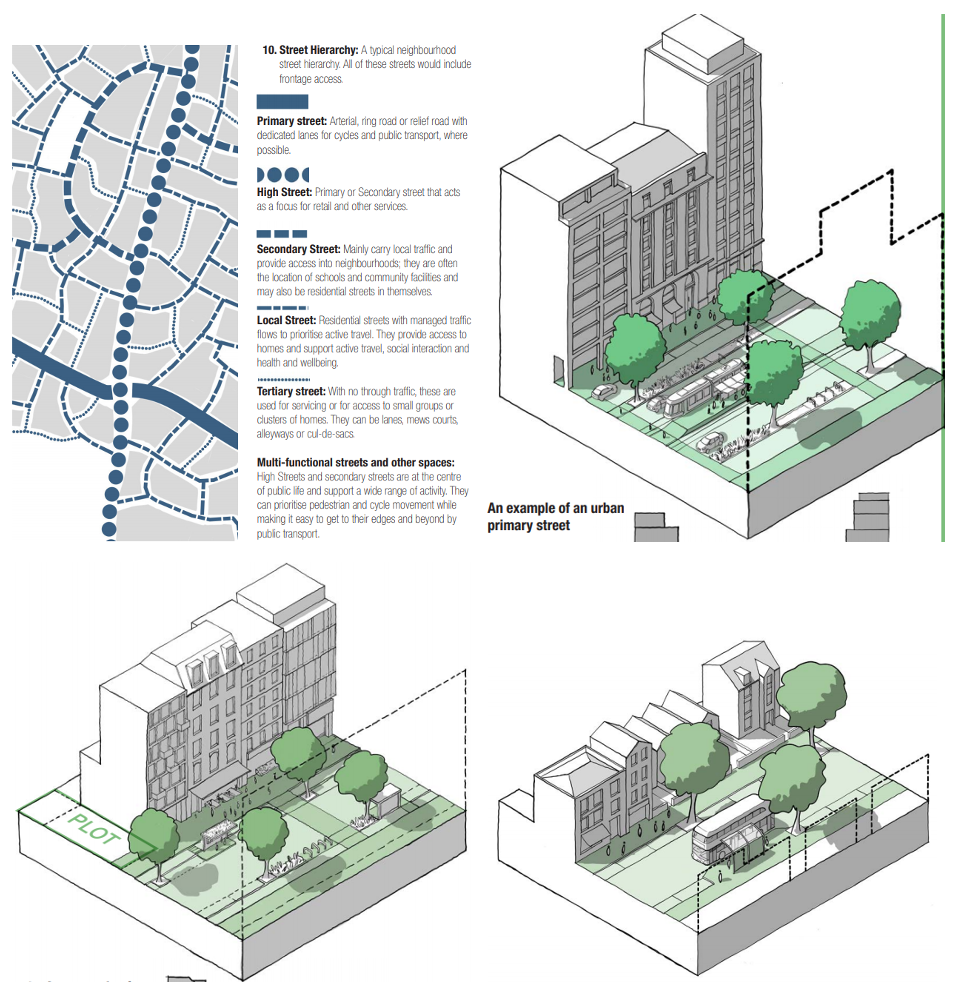

This approach should be integrated with the proposed Guidance Notes for Design Codes where the Movement and Public Space sections explicitly provide for the consideration of actual walking distances for bus stops (considered to be around 5 minutes) in the definition of the mix of land-uses, location of amenities, densities, as well as connected and hierarchical road networks (as opposed to cul-de-sacs) and public transport priority measures along the main routes.

(source: Guidance Notes for Design Codes, MHCLG, 2021

Both the bus strategy and the design codes recognise that too often the lack of bus prioritisation on main routes and on main roads detract from the network quality, with buses stuck in congestion and queues, increasing journey times and thereby the required fleet size (and therefore the cost) to provide the service. The strategy therefore brings powers to local authorities to develop key route networks where significant space reallocation is expected towards public transport such as bus priority measures from signal priority, to bus gates, to continuous bus lanes. The strategy also supports the provision of bus rapid transit systems (with a high level of segregation) on key corridors, and intermediate ‘superbus networks’ with a high level of service for low density, yet not rural, areas (defined as ‘patchworks of towns and villages’)

Finally, to support the move to a zero-carbon society and to improve both the image and accessibility of the bus network, the strategy includes a reform of the Bus Service Operators Grant, currently working as a fuel subsidy, to include electric buses, as well as funding to help purchase 4,000 zero emission buses (10% of the national fleet). The strategy includes provisions to support innovation and technology and the provision or improvement of emand Responsive Transit systems in low density areas, without hiding the difficulties of developing an economically viable operational model.

Despite the £3billion package that underpins the strategy (through multiple years), the funding of bus services remains a challenge even in London (buses are one of the main contributors to TfL’s deficit). Privatisation did not deliver cross-funding (ie profitable routes supporting non-profitable, but socially-necessary, routes) with operators withdrawing from non-profitable areas and leaving councils with shrinking budgets to pick up the bill. The development of franchising or enhanced partnership involving local authorities in the development of the network, and underpinned by clear contracts and binding agreements, could help to deliver this cross-subsidy. However the London experience suggests that the profitable routes will not entirely cover the costs. Funding will also remain significantly centralised, reducing local authority flexibility in adapting to local circumstances. Finally, neither the national design codes, or the planning white paper, or indeed the national bus strategy consider or clarify how development contribution can integrate with bus provision: often, development contribution only covers the first few years of services, which then disappear once the contribution finishes due to lack of funding.

The need to reduce and control operational costs is present throughout the strategy, however this might end up being in contrast with (and undermine) other aims, such as the provision of extended evening and weekend services to towns and villages. While on paper it is good to focus public funding in capital investments rather than subsidy, in my opinion, too much focus on balancing operational sheets presents a high risk of reducing improvements in wider accessibility: despite vague aspirations, there is no firm commitment on what levels of service should be provided to towns and villages. For example, in the Zurich region the minimum provision is for hourly services from 6am to midnight for all settlements with at least 300 inhabitants. Ideally, there should be something comparable for English settlements.

While a significant public investment (which could be optimised by an integrated approach to planning, transport and design by focussing well-connected development along new or existing bus corridors), the implications of such a commitment for smaller, isolated communities for access to jobs, education, cultural, economic and social opportunities, and access for visitors, could be transformational.

In conclusion, the national bus strategy can provide a foundation for a more integrated transport and development planning system if used wisely together with the Planning for the Future white paper, the Gear for Change document and the Guidance for Design Codes.

As the planning bill is brought before Parliament with the full set of reforms, possibly this autumn, local authorities will need to carefully integrate bus service provision into their design coding and zoning plans. Although parts of these changes are controversial (in particular with respect to consultation, community involvement, local authority control over the quality of interventions and a potentially significant underestimation of transport patterns, mode choice and the impact of not getting things right at masterplanning stage – as highlighted by Transport for New Homes and other organisations), they give local authorities a new set of guidance and powers that can allow, if used wisely and in an integrated way, for an improved coordinated transport-land use planning approach.

We’re looking forward to working alongside our transport operator, developer and local authority clients to make the most of these new policies and deliver people-centred and sustainable urban development across the UK.